If the kids can’t go to the library, the library has to go to the kids

Written by Dave Roche

June 07, 2021

This was a year of building. This was a year of re-imagining, experimenting, listening, problem solving, and creating. For those of us fortunate enough to make it through this year shaken, bruised, but still smiling, it was our obligation to share our hope with those who had run out. It was our duty to ease the burden of those about to break. This was not a time for sifting through the ashes of the year hoping to find something salvageable from the old normal. This was a time to create something better, expect something more, and work like you’ve never worked before to get it.

And the talk of learning loss? This year was a Rorschach test; you saw what you expected to see. I saw students navigate multiple online tools. I saw students create websites. I saw students problem solve tech issues. I saw students learn how to manage their time, stick to a schedule, and keep their classwork organized far beyond what I was ever able to teach. I watched as students learned to advocate for themselves, learned how to ask for support, and support each other. I watched as day by day they became more resilient and more confident. OK, they might not be able to identify consonance in a poem, but they made incredible gains in executive functioning, creativity, technological know-how, and emotional awareness.

This was a year where I tried to let the students tell me what they need and I would provide the resources. And one thing I noticed students needed was books. Many of my students did not have books at home, and those who had books had already read them. Learning remotely, they had no classroom or school libraries to borrow from, and going to public libraries was probably questionable for families who were concerned about exposure to the virus (or who didn’t have the time or energy to go to the library.) As a reading teacher, the one thing I want more than anything else is for my kids to be reading all the time. So if kids can’t get to our books, then we should get our books to kids.

That’s why I decided to make a bookmobile. Now, some people might think not having a car or even a driver’s license would be a major, maybe insurmountable hurdle, to starting a bookmobile. I wasn’t going to let that stop me. I have a bike.

I bought a sturdy bike trailer, one capable of carrying 100 pounds. This was also about the limit my legs could pedal. I mean, in my 20’s I could have biked the whole Independence Park Regional Branch around town, but I’ve been sitting in front of a computer for 10+ hours a day for the past 15 months. I’m not in my best biking shape.

Next I had to build a bookshelf, something I could fold up so it wouldn’t tip over while riding. I asked my father for help. To say he did 90% of the work might be underestimating.

Then it was my favorite part of planning: buying books. I put in a $350 order to Women and Children First (my favorite bookshop in Chicago) and a $150 order to Scholastic. I love buying books, but the joy I get from buying a ton of books knowing I will get reimbursed for them? OFF THE CHARTS. Graphic novels, poetry, historical fiction, nonfiction… I even got a cookbook. As this was a family literacy event, I wanted to make sure I had books for parents as well. I took a few titles from my personal collection and added them to the shelves.

For my debut, my school’s music teacher was nice enough to let me set up at her outdoor, socially-distanced production of Little Shop of Horrors. I gave a little speech about it before the show, and after the show several families came by and checked out books. They seemed to really like the idea.

First borrowers

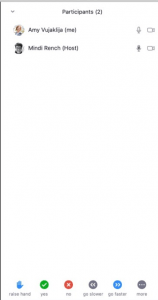

But the purpose of the bookmobile is to take the books to students, not to have them come to me. The principal let me write up a blurb about the bookmobile for the weekly parent newsletter. Several families were interested. I got their information, made up a Google map of their houses, and planned my route.

For some reason I chose a 90° day to make my first trip out to families’ houses with the bookmobile. It went better than I expected! Kids were happy to get some new books, and I think they got a kick out of seeing one of their teachers out in the real world. Parents loved the idea and one checked out a book for herself. And one of the really nice things is, I’ve already had several parents and a few teachers offer to donate books. I might need to buy another bike trailer and take on an intern!

First trip to a family’s house

I intend to take the bookmobile out throughout the summer. The goal is to get more parents interested and have a set route I cover every two or three weeks, picking up old books and lending out new ones.

Every aspect of the bookmobile has brought me joy. And even if I don’t end up on the news like people keep telling me, I’m glad that good books are making their way into the hands of good readers.

By Featured Writer Steve Zemelman

By Featured Writer Steve Zemelman

Consider using this technique to search memories for details about past experiences, reconstruct scenes from stories (or combinations of stories), or create new, imaginative experiences. You may be surprised what you can come up with!

Because guided imagery works so well, evoking vivid details which people have often forgotten, and because it requires some rather carefully worked out methods, Zemelman and Daniels wrote a whole chapter about this procedure in

Consider using this technique to search memories for details about past experiences, reconstruct scenes from stories (or combinations of stories), or create new, imaginative experiences. You may be surprised what you can come up with!

Because guided imagery works so well, evoking vivid details which people have often forgotten, and because it requires some rather carefully worked out methods, Zemelman and Daniels wrote a whole chapter about this procedure in  So how might the writing marathon be modified for the classroom or home when mobility is limited? When conducting a writing marathon in a limited space such as around the classroom or home, consider guiding participants to find inspiring spaces or objects. Lately, scavenger hunts have become popular activities. Similarly, writing can be inspired by reflections about the simplest objects in our local spaces – birds in flight, spring awakening, cracks in sidewalks (where did old wives’ tales come from, anyway?).

So how might the writing marathon be modified for the classroom or home when mobility is limited? When conducting a writing marathon in a limited space such as around the classroom or home, consider guiding participants to find inspiring spaces or objects. Lately, scavenger hunts have become popular activities. Similarly, writing can be inspired by reflections about the simplest objects in our local spaces – birds in flight, spring awakening, cracks in sidewalks (where did old wives’ tales come from, anyway?).

Some poems take the form of “direct address”—that is, the speaker in the poem talks directly to a specific person. Poems can be used to develop initial reactions to situations or current events or as extensions of

Some poems take the form of “direct address”—that is, the speaker in the poem talks directly to a specific person. Poems can be used to develop initial reactions to situations or current events or as extensions of