Writing to Learn into the Content

Using writing to learn activities to think through content is useful for beginning units, accessing prior knowledge, and making predictions. Consider the carousel brainstorming method for engaging students in particular questions about the topic. See how you can adapt this activity for both face-to-face and virtual settings.

Carousel Brainstorming: Face-to-Face

- Write five or six statements or questions about the topic being studied – each one at the top of a separate piece of chart paper.

- Post charts with statements or questions around the room.

- Option 1: Students in small groups rotate among the posted sheets, and each group spends several minutes at a sheet to discuss the topic and then write a group brainstorm or response on the chart paper (and sign it).

- Option 2: Students individually write comments on chart paper as written conversations. If approaching the task as an individual activity, chart paper should be placed on tables to be more easily accessible by multiple students at once.

- At your signal, the groups rotate to the next chart.

- Repeat until all have visited all the charts.

- Allow a few minutes for a gallery walk for people to see all the ideas that have been shared.

As with other brainstorming, use the lists as you are working through the unit, to highlight big ideas and themes, answer questions, or clarify misconceptions.

Carousel brainstorming in face-to-face classroom or conference environment invites both written and verbal conversation.

Carousel Brainstorming: Virtual

A platform such as Padlet.com provides a collaborative virtual bulletin board. On Padlet, the “shelf” template allows you to title columns with statements or questions.

- Make a Padlet board* with a template such as “shelf.”

- Write 5-6 statements or questions, each on a different column in the Padlet board.

- Students read and respond to all of the statements and questions in a set amount of time.

- During the next time frame, students may select one statement or question for their focus.

- Student read all the posts made in this focus column.

- Invite students to comment on a few posts that particularly connected to them.

- Extend this activity by asking students to summarize thoughts in a journal entry.

- When using the carousel writing to learn activity for moving into the content, be sure to return to the activity at the end of the unit or topic. Using new chart paper or Padlet allows for comparisons to students’ original thinking. You can also clear the original Padlet, but be sure to save the original as a PDF!

Happy thinking and writing!

*Note: Carefully consider the settings for the age/grade level. Padlet allows for anonymous posts, but the settings can be changed to require authors’ names and allow comments from other participants. Settings also provide the option to moderate posts and filter for profanity. Virtual participation often results in more boldness than face-to-face classroom interactions, which are both advantages and disadvantages to the digital platform.

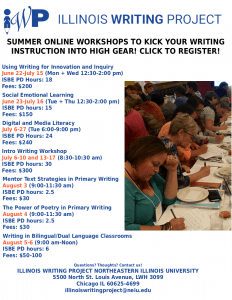

Resources provided by the Illinois Writing Project Basic 30 Team. Become part of our community – see our upcoming events here. Check out IWP on Twitter!

Consider using this technique to search memories for details about past experiences, reconstruct scenes from stories (or combinations of stories), or create new, imaginative experiences. You may be surprised what you can come up with!

Because guided imagery works so well, evoking vivid details which people have often forgotten, and because it requires some rather carefully worked out methods, Zemelman and Daniels wrote a whole chapter about this procedure in

Consider using this technique to search memories for details about past experiences, reconstruct scenes from stories (or combinations of stories), or create new, imaginative experiences. You may be surprised what you can come up with!

Because guided imagery works so well, evoking vivid details which people have often forgotten, and because it requires some rather carefully worked out methods, Zemelman and Daniels wrote a whole chapter about this procedure in  So how might the writing marathon be modified for the classroom or home when mobility is limited? When conducting a writing marathon in a limited space such as around the classroom or home, consider guiding participants to find inspiring spaces or objects. Lately, scavenger hunts have become popular activities. Similarly, writing can be inspired by reflections about the simplest objects in our local spaces – birds in flight, spring awakening, cracks in sidewalks (where did old wives’ tales come from, anyway?).

So how might the writing marathon be modified for the classroom or home when mobility is limited? When conducting a writing marathon in a limited space such as around the classroom or home, consider guiding participants to find inspiring spaces or objects. Lately, scavenger hunts have become popular activities. Similarly, writing can be inspired by reflections about the simplest objects in our local spaces – birds in flight, spring awakening, cracks in sidewalks (where did old wives’ tales come from, anyway?).

Some poems take the form of “direct address”—that is, the speaker in the poem talks directly to a specific person. Poems can be used to develop initial reactions to situations or current events or as extensions of

Some poems take the form of “direct address”—that is, the speaker in the poem talks directly to a specific person. Poems can be used to develop initial reactions to situations or current events or as extensions of